About a year ago, I was in a class which analyzed melodrama in terms of film theory. The course was heavy-laden with emotion, family, home, and concepts which challenged our ideas of melodrama and its audiences. Each time the class would reconvene, our professor would ask us if we cried (I did a few times!) and I was always fascinated to see which films conjured tears for my classmates. Among the films chosen for the course, we heavily studied the films of Douglas Sirk — his name goes hand-in-hand with melodrama.

Douglas Sirk has influenced directors for years following his hey-day in the 1950s — though, Sirk was not appreciated until his films were analyzed in retrospect. You can find hints of his trademarks in the works of Quentin Tarantino (Pulp Fiction), Pedro Almodovar (All About My Mother), Lars von Trier (Dancer in the Dark), and Todd Haynes (Far from Heaven). Today, I thought I would give a run-down of Douglas Sirk’s style and his status as an auteur (yes, there’s that word again!).

First of all, what makes up a Sirkian melodrama? Or, better yet, what makes up a melodrama? There are key themes of motherhood, emotion, a sense of loss, families, clear distinctions of good and evil… among many other elements which create melodrama. The key thing to recognizing a melodrama, for me, is the need for a Kleenex box. These elements can be found in Sirk’s films, but he has his own level of classification in the mode of melodrama. I’ll describe two of them: distanciation and use of colour.

Distanciation

One of the more daunting aspects of film studies is understanding distanciation. Part of the Classical Hollywood formula of filmmaking is being completely and utterly absorbed in the plot to the point of escapism. Some directors like to challenge this notion of escapism (such as Lars von Trier, think of the beginning of Europa). Distanciation is anything that makes the viewer uncomfortable or alienated from the film. Sirk uses various techniques for distancing his audience from the characters within the film. His scenes are very divided, boxed-in, and isolating for the characters. This style of filmmaking requires the audience to step away from self-identification with the characters.

Jane Wyman’s character, Cary, in All That Heaven Allows gazes into a brand-new television. She is boxed-in and distanced from the world around her.

Colour

Sirk is best known for his use of colour and this trademark has been passed onto the aforementioned directors. As I said in a previous blog, Wes Anderson uses a palette of colour for every film to make his shots seem picturesque. I think the same can be said about Sirk, but on a different level. Sirk’s use of colour has meaning and each shot is meant to represent something deeper than the dialogue on the surface.

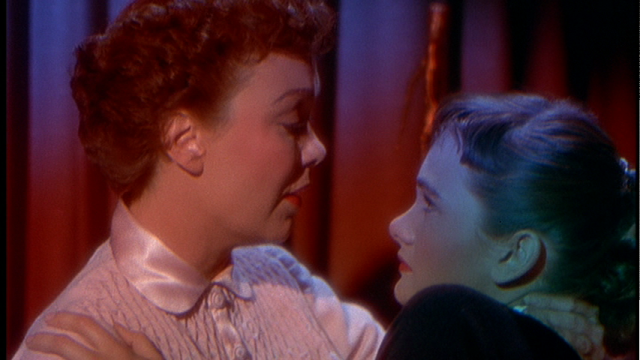

Cary (Jane Wyman) tries to relate her daughter. The reds and the blues indicate the tone of the scene.

I used stills from All That Heaven Allows because I would like to analyze Sirk’s influence on Todd Haynes’ film Far From Heaven in tomorrow’s blog. The films and their content are very similar… and who doesn’t want to talk a little bit about Julianne Moore? So, has anyone seen a Douglas Sirk film? Do you have a favourite melodrama?

Interesting